The Language of Solomiya Krushelnytska’s Culinary Recipes: A Reportage Essay

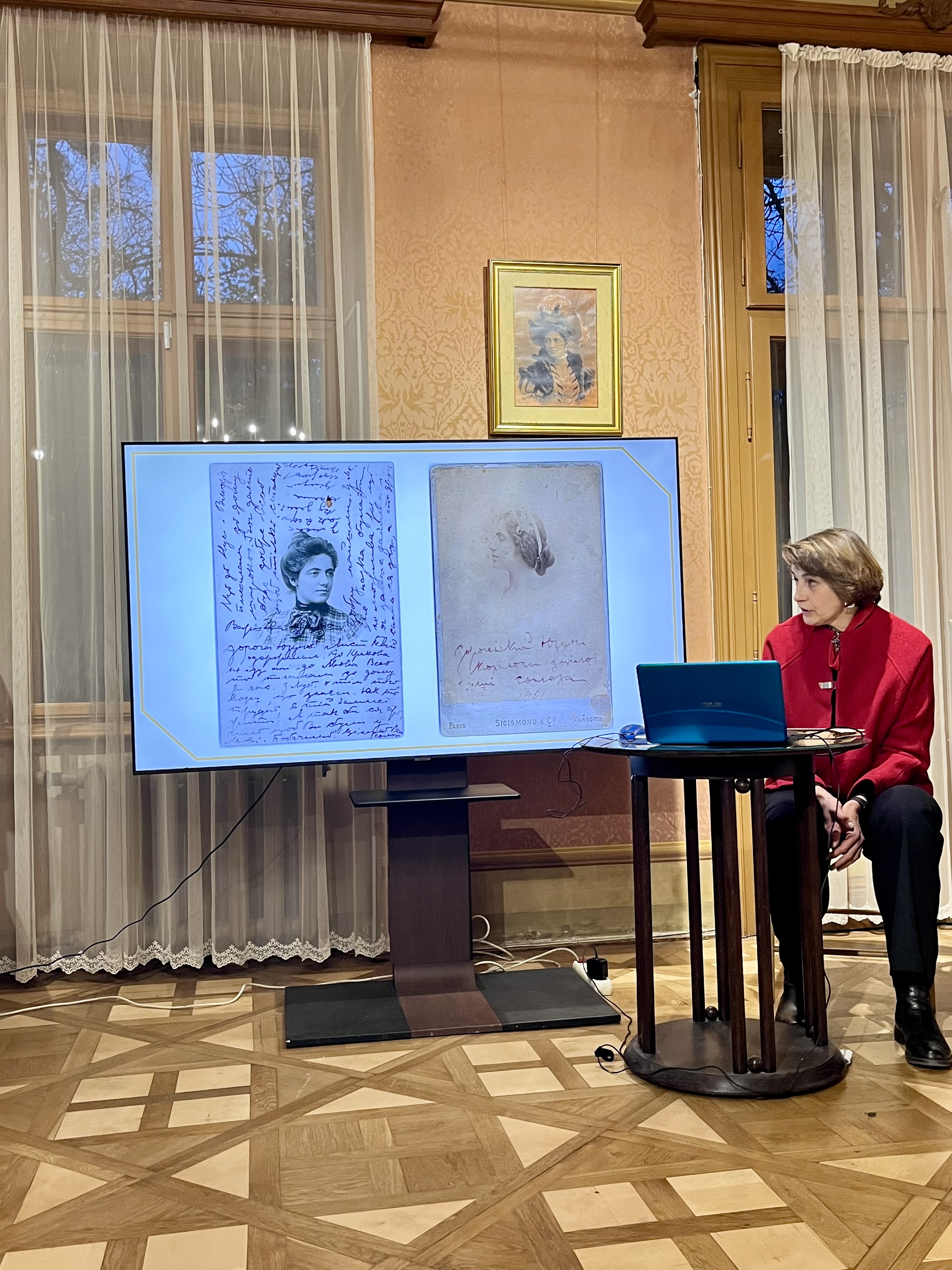

Lecture at the Solomiya Krushelnytska Museum

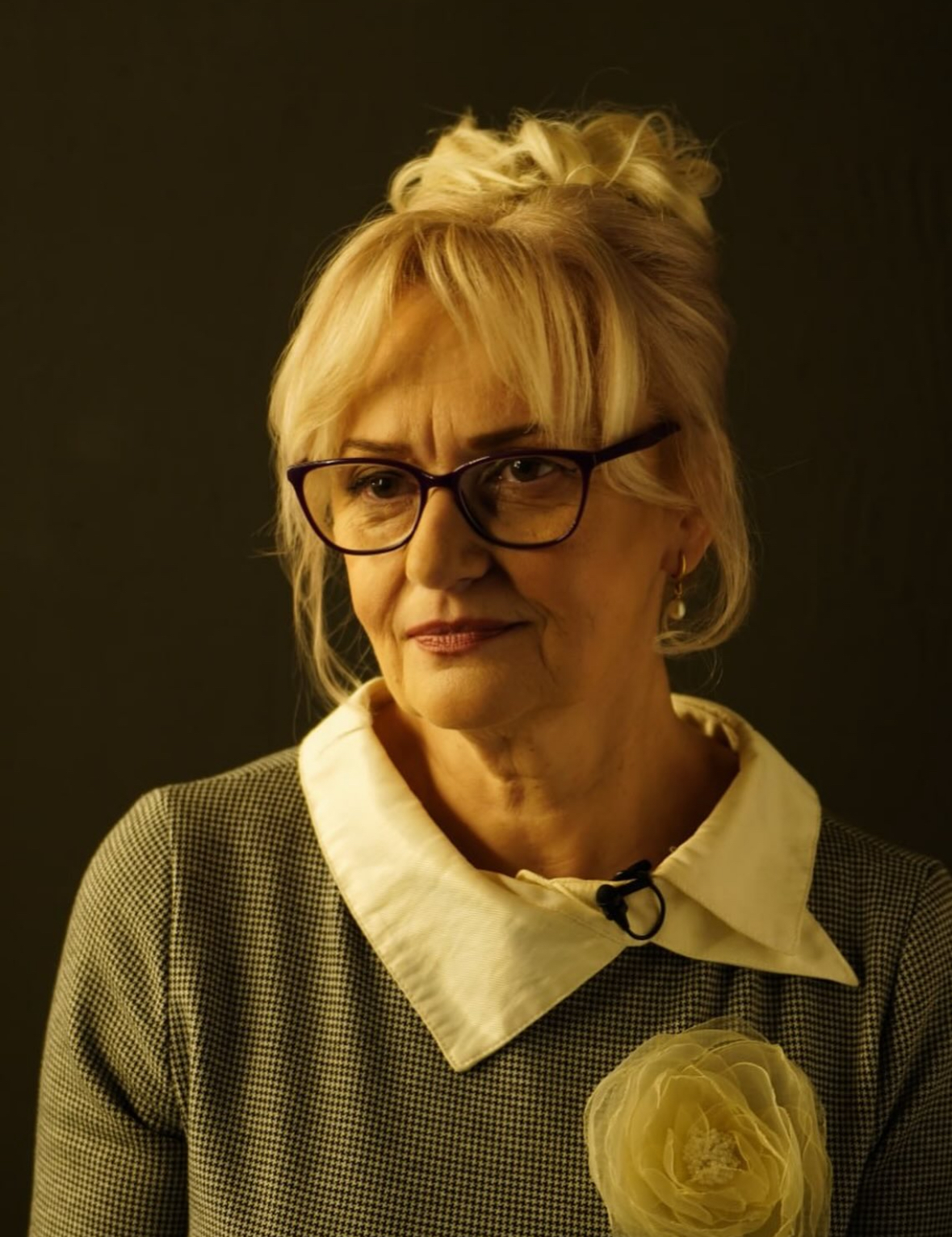

On Sunday, 2 November 2025, the Solomiya Krushelnytska Museum in Lviv invited visitors to an unusual lecture. As part of the Days of Ukrainian Literacy and Language, senior researcher Halyna Ohorchak spoke about how culinary recipes are part of history: they preserve vocabulary, measurements, social codes and even family legends. The lecture “The Language of Solomiya Krushelnytska’s Culinary Recipes” opened up the artist’s domestic world for the audience. Ms Halyna explained which units of weight and volume were used by housewives in the past, what familiar kitchen utensils were called and how these words shaped the era’s flavour. She also referred to the culinary notes of Vira Franko and other families to recreate the atmosphere of domestic life among artists and intellectuals. The researcher reminded listeners that family recipes circulated in a narrow circle; sometimes families did not even share certain recipes – which is why enigmatic dish names such as Camaldolese roast have remained in the memory of visitors.

Olya Boiko, manager of the “Barista School” at the Ukrainian School of Hospitality, attended the lecture. Her presence underscored that old recipes matter to the modern restaurant business: studying culinary history helps service remain both authentic and innovative.

The Rich and Varied World of “Priestly Cuisine”

The first minutes of the meeting outlined the scale of what scholars call “priestly cuisine.” In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Ukrainian Greek‑Catholic priests belonged to the wealthy class: their families travelled to seminaries in Vienna and Rome, took recipes from Jewish, Hungarian and Armenian neighbours and combined those influences with traditional Ukrainian dishes. In villages, few had seen the medal cake, yet at festive tables of priestly families one might even find Camaldolese “roast,” a vegetarian dish of white mushrooms whose recipe came from the monastic Camaldolese order. This order, founded in 1012 near Arezzo in Italy, combined a hermit’s way of life with an ascetic monastic rule; its cuisine favoured dishes made from forest mushrooms because the monks did not eat meat. Ms Ohorchak recalled that the Krypyakevych family prepared this roast only on the biggest holidays because it was so complex and expensive.

The gentry of priestly families in Galicia were wealthy and mobile. Theological seminaries in Vienna or Rome served not only as schools of theology but also as sources of new culinary ideas. When setting out on holiday, priests and their wives brought home recipes from Jewish, Hungarian, Armenian and Italian cuisines. That is why archival records contain dishes that today seem exotic. One of them is the Camaldolese roast, which Ms Halyna’s colleague, researcher Dariya Ohorchak, mentioned during the lecture. As a child she heard that this fragrant mushroom roulade was made by the Camaldolese monks (Italian hermits) who practised strict fasting. According to legend, the Camaldolese roast contained only white mushrooms, cream and aromatic spices, but it was so rich that, as Ms Dariya joked, “meat would probably have been cheaper.” When museum worker Adriana Hurchak, a renowned researcher of Krushelnytska’s cuisine, died in 2021, historian Lesya Krypyakevych called Ms Ohorchak asking her to find the Camaldolese roast recipe in the notebooks. It could not be located, but the story itself showed how deeply this dish had taken root in family memory. The Camaldolese roast is a vegetarian dish of white mushrooms invented by the Camaldolese monks; it requires much time and expense and was cooked only for major holidays.

Despite the aristocratic menu, housewives did not shy away from order and precision. The kitchens of these houses were well equipped, had several maids and plenty of tableware. Children participated in the household from an early age: Solomiya Krushelnytska had to feed the chickens and geese, but according to her sisters’ recollections she often hid behind the piano – her parents allowed her not to be pulled away from playing and singing. Thus a balance between art and everyday work was formed. The singer’s niece Yaroslava Muzyka recalled that in the villa in Viareggio “Krushelnytska could create a cosy corner for herself; there she did not disdain household management or the kitchen, which she busily attended to. Her house was characterised by exemplary order and precision.”

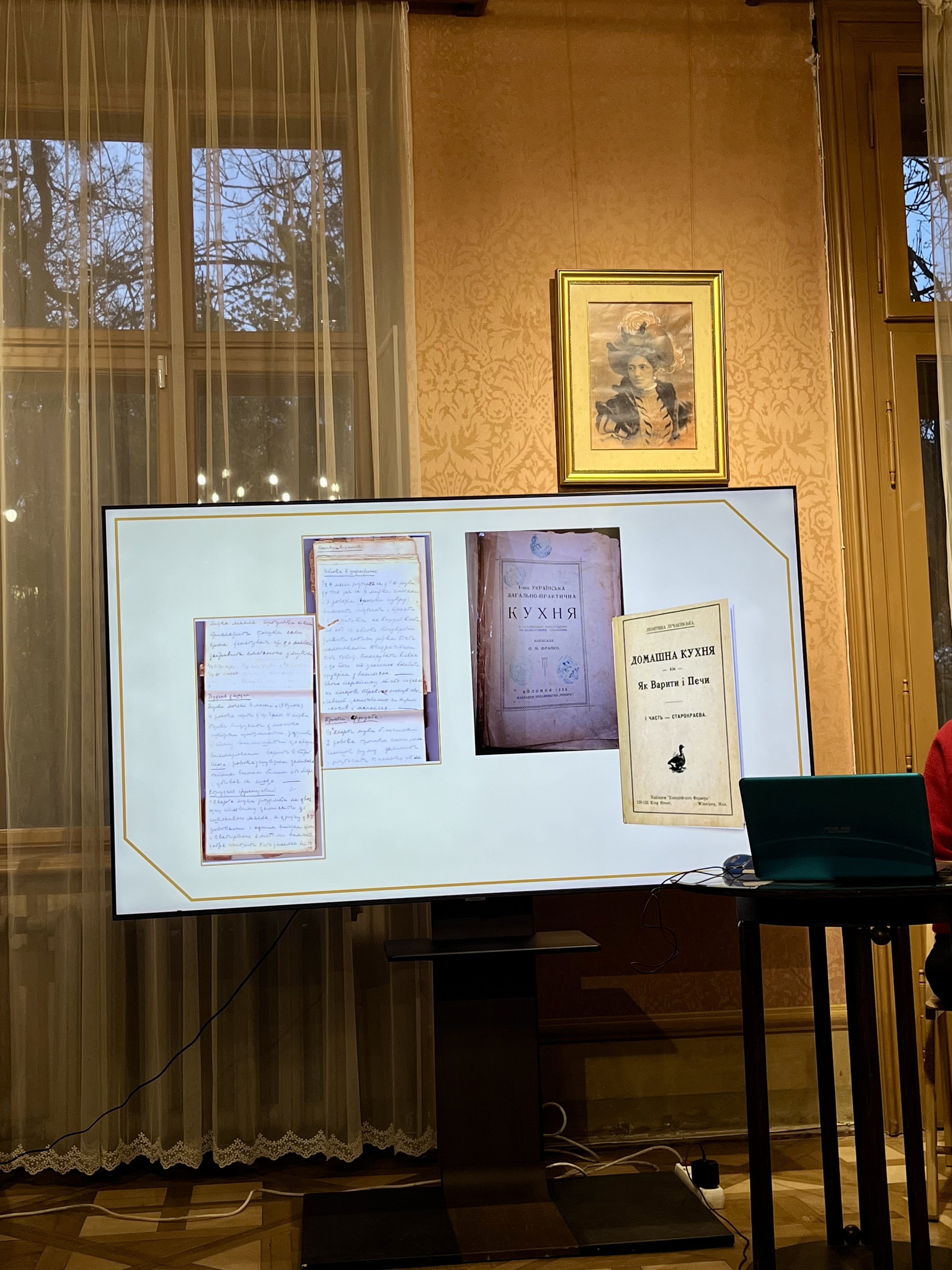

Solomiya Krushelnytska’s Notebook: Language, Styles and Mysterious Words

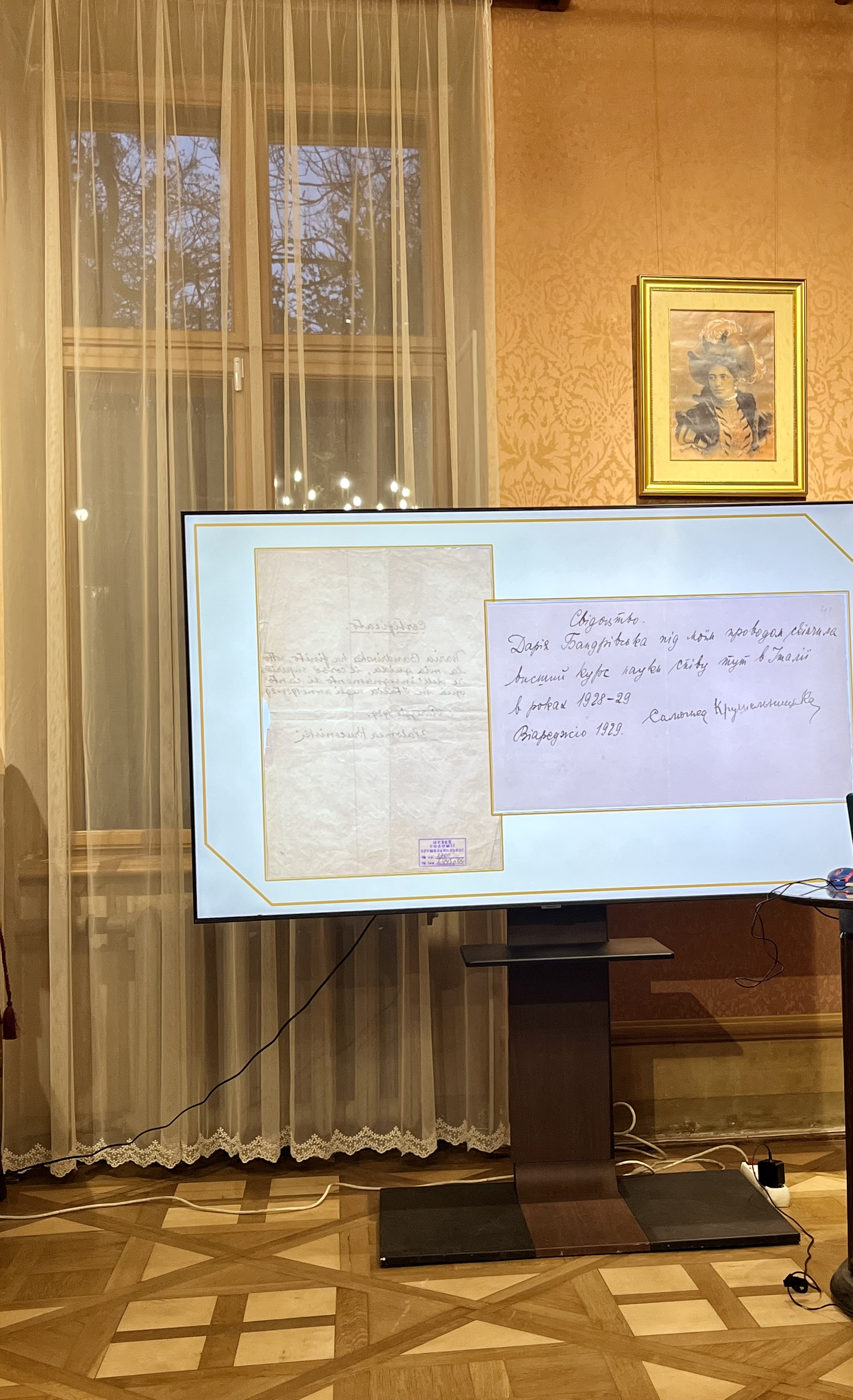

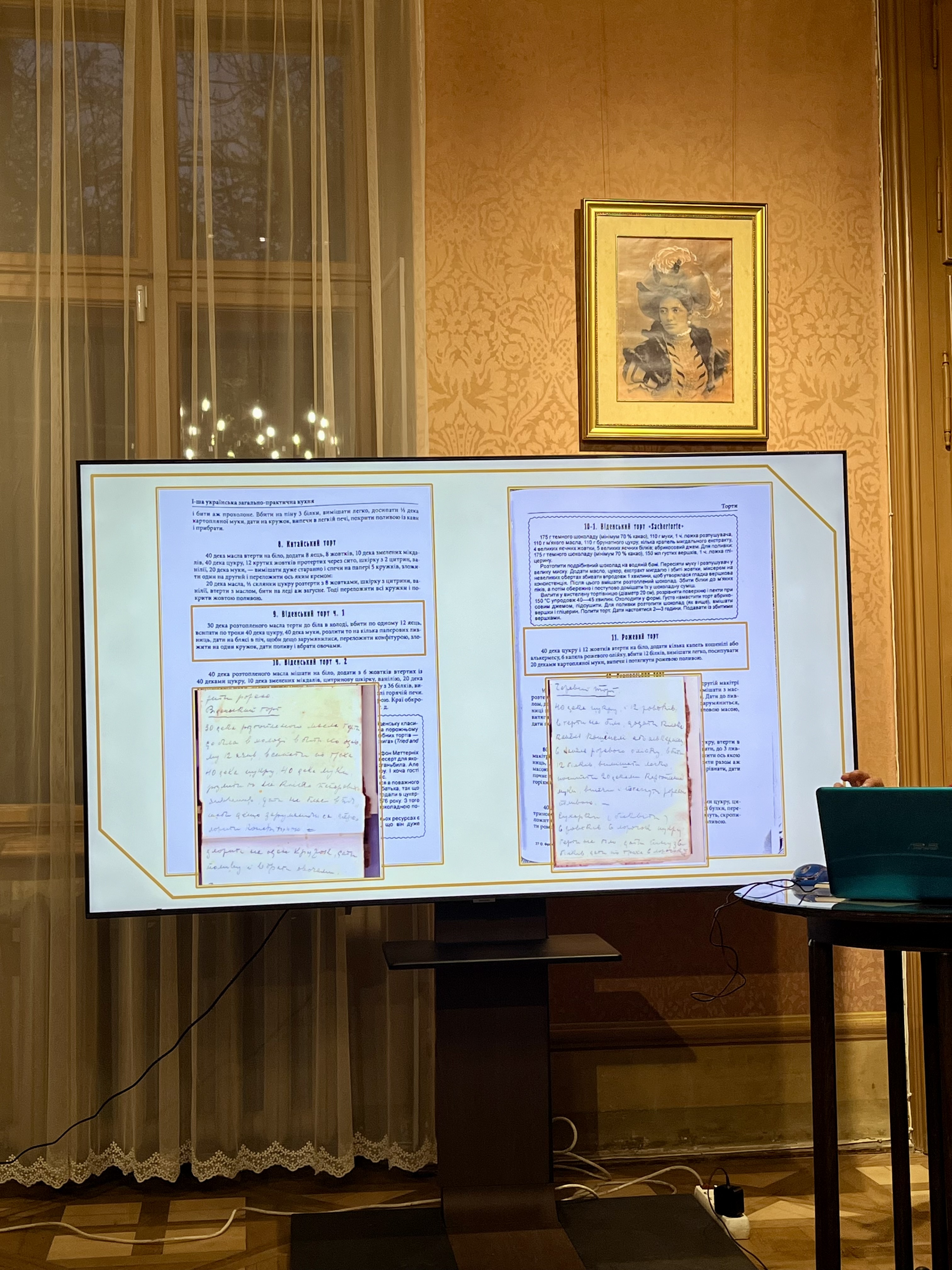

At the heart of the lecture lies a unique culinary notebook that Krushelnytska began keeping, presumably in the 1920s. After concluding her opera career she settled in the town of Viareggio and wanted to recreate the taste of her parental home. The notebook contains more than seventy recipes, mainly for pastries. The presenter explained that many recipes the singer apparently wrote down not for herself but for her cook Enma: sisters and nieces recalled that in Italy Solomiya seldom stood by the stove herself, but she always indicated what she wanted on the table. Therefore, the recipes are short, sometimes without exact proportions: they are intended for an experienced housewife who knows the basics of technique.

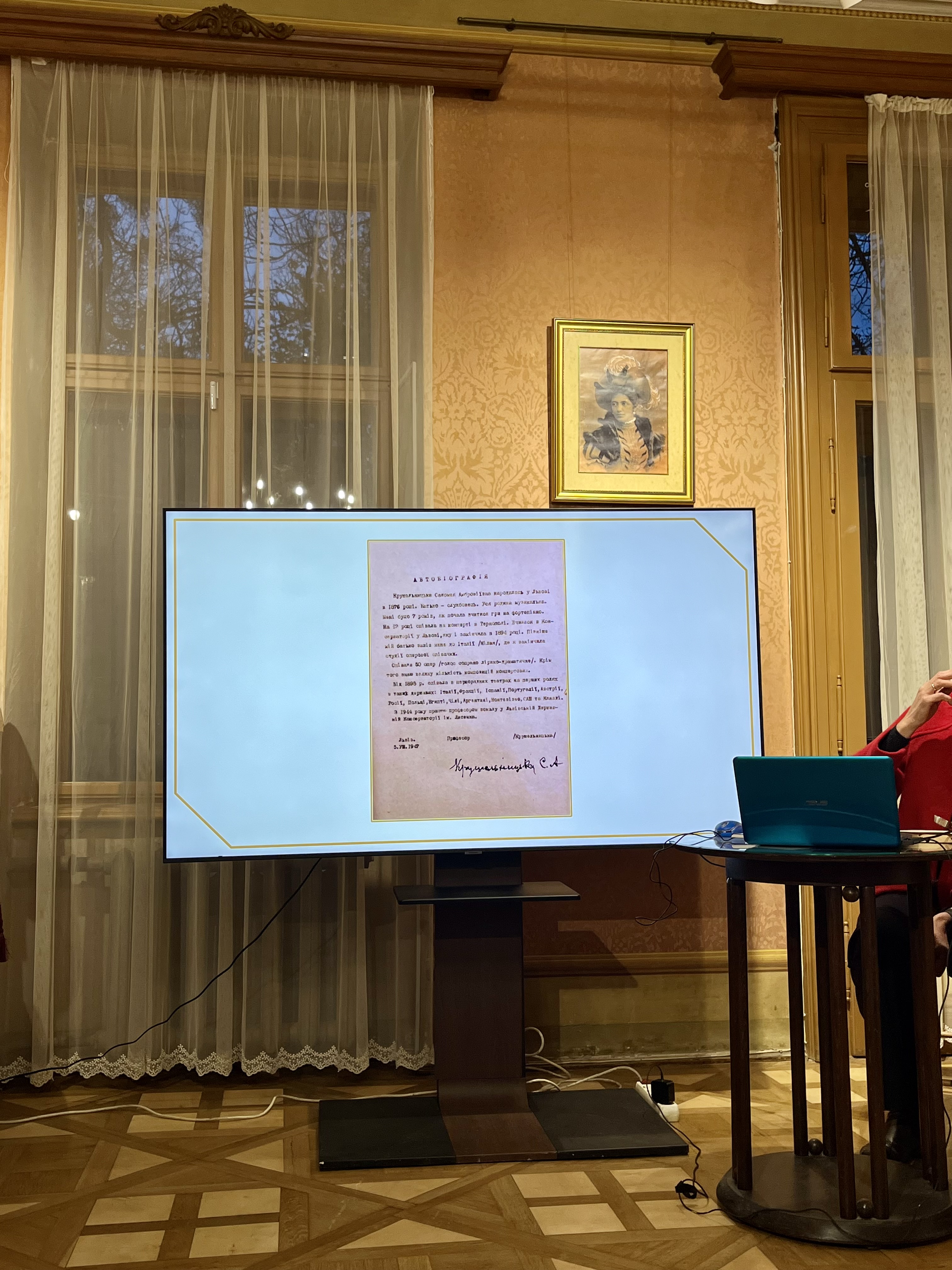

Ms Ohorchak said that the authenticity of the records was confirmed by graphologists of the Security Service of Ukraine: they compared the handwriting in the recipes with known letters of the singer. Yet it is difficult to determine the date of each page because Krushelnytska knew seven languages and easily switched from one to another. In pre‑war documents she admitted that she was less fluent in English and Russian, whereas she knew Polish, Italian, German, Spanish and French well. The culinary notes are mainly in Ukrainian, but there are Polonisms and Germanisms – “ledy/lody” (ice cream), “dinstovani” (stewed) and “buden” (a cabbage dish, not related to the English pudding). According to her niece Odarka Bandrivska, Solomiya’s writing style was laconic and even telegraphic: she preserved her voice, economised on time and wrote briefly, to the point. This is also evident in the recipes: “Bake 25–30 minutes,” “Beat the egg white with sugar” – without unnecessary words.

The notebook contains mostly sweet dishes: cakes, biscuits, “ledy‑lody” (what they called ice cream), sorbets, but also simple fare such as lazy dumplings or cabbage soup. The lecturer explained that certain words require explanation. For example:

- “Dinstovani ovoche” (from the German dünsten) – stewed vegetables; in Galicia “ovoche” referred to fruits, while what we now call vegetables was called yarina.

- Budyn (buden) – a dish of stewed cabbage or other vegetables; it has nothing to do with the English pudding.

- Laginina / ligumina – an old dessert of whipped egg whites, nuts and jelly; the name derives from the Latin legumen, “legume.”

- Olyvnytsia – a mould for baking cakes, a type of cake tin; the word comes from the practice of oiling the tin.

- Ledy‑lody – an archaic term meaning ice cream; it appears alongside “morozhene” (ice cream) in the notebook, which captures the evolution of the lexicon.

One of the most striking recipes in the notebook is the “pink cake,” in which the dough is coloured with the Italian liqueur Alchermes made using the carmine dye kermes. Such a cake was likely baked for celebrations or during tours in Italy. Some recipes turned out to be identical to those in Olha Franko’s Practical Cookery. In 1929 the “Record” publishing house in Kolomyia brought out her First Ukrainian General‑Practical Cookery running over 500 pages. The author, the wife of Petro Franko, studied gastronomy in courses in Vienna and collected recipes from priestly families. Parallels between the notebook and the book show that women freely exchanged recipes, though some family secrets remained hidden.

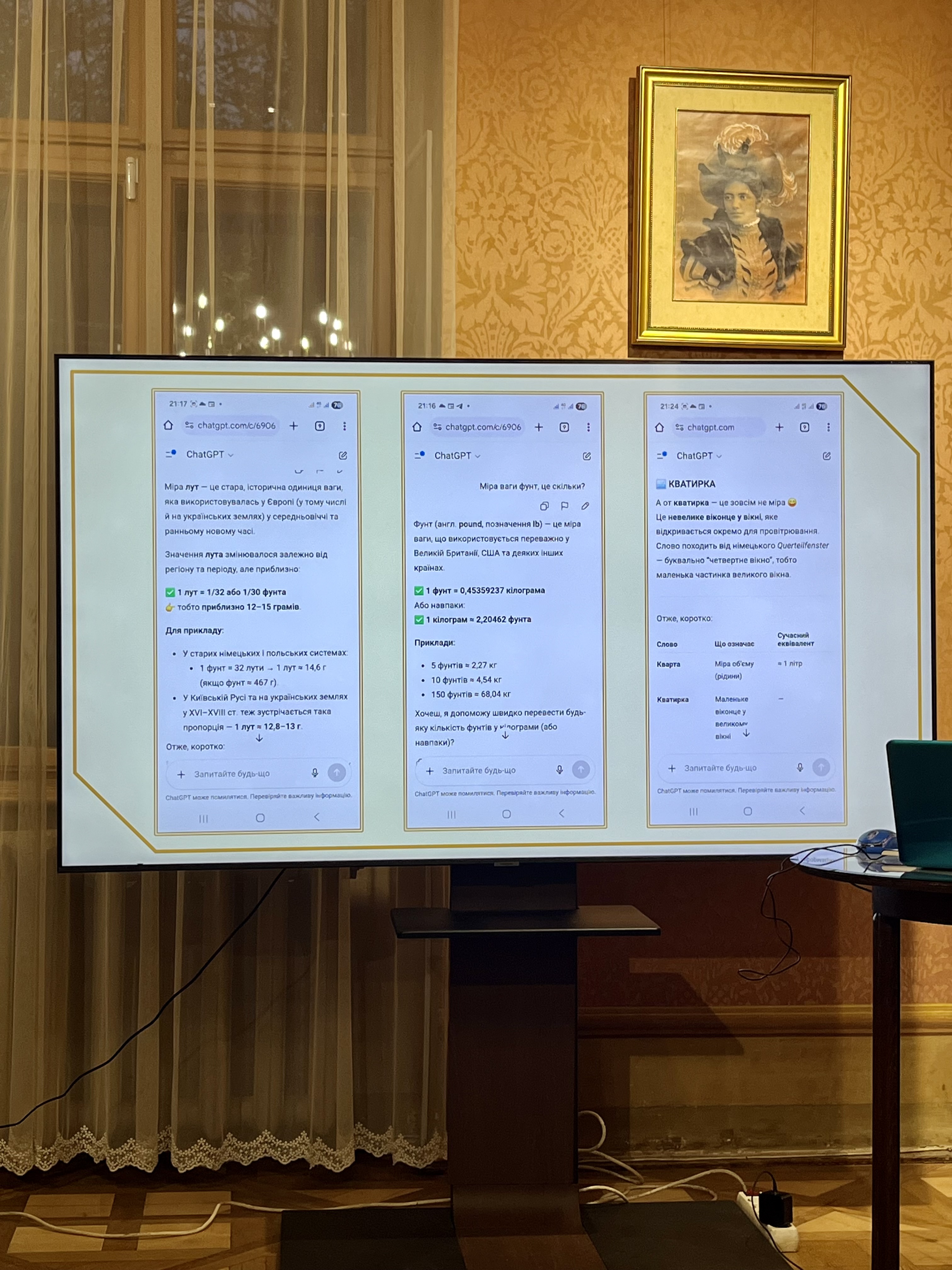

Halyna Ohorchak paid particular attention to units of weight and volume. In Solomiya’s notebook one finds such measures as lot (about 12.8 g), funt (half a modern kilogram), kvarta and harnets (measures for liquids), chetvertina, quarterka, luk and kuflik – volumes that varied by region. Housewives also used wooden ladles known as pivka or fuksa. The lecture became a journey through the language of cookery: today’s obvious words once meant something else. In the 1920s and 1930s “ovoche” meant fruit, while what we now call vegetables was known as yarina. Even basic terms were recorded differently: “morozhene” (ice cream) co‑existed with the Polonism lody, while ledy meant a frozen dessert. Although these concepts have largely been forgotten, they let us feel the domestic life and language of a century ago.

When Recipes Become History

Halyna Ohorchak emphasised that culinary recipes are not only methods of preparation but also repositories of memory. They convey everyday life, social status and community ties. Priestly families could afford expensive products, taught children etiquette and cookery, and Solomiya Krushelnytska had to learn to cook before becoming a priest’s wife. Yet she chose the stage and became an opera diva. In later life her culinary notebook helped her preserve a sense of home in her villa in Viareggio: niece Yaroslava Muzyka recalled that the house on the coast was characterised by exemplary order, and maids consulted Ms Solomiya every day about what to cook for lunch or dinner.

At the end of the lecture, attendees returned to the issue of cultural codes. Participants recalled that gastronomic symbols can be weapons of imperial propaganda, as happened with the Pavlova dessert named after a Russian ballerina. In response, Ukrainian chefs created an alternative – the Karinska dessert. This mini‑cake shaped like a ballet tutu is dedicated to Varvara Karinska, who created the modern tutu and became the first Ukrainian woman to win an Oscar for her costumes for the film Joan of Arc. Pastry chef Myroslava Novosad, restaurateur Yevhen Klopotenko and restaurant consultant Vsevolod Polishchuk developed the recipe from meringue with buckwheat powder, sour cream, cream and cherry compote. The dessert does not deny the Pavlova but offers an alternative that reflects Ukrainian identity.

Who Was Varvara Karinska?

The name of Varvara Andriivna Karinska was heard both at the lecture and in the context of the dessert. She was born in Kharkiv in 1886, studied at Kharkiv University as a free listener, and after emigrating she became a world‑class costume designer. Karinska revolutionised ballet fashion: her tutu combined ten layers of chiffon of different lengths, making the costume lighter and allowing ballerinas greater freedom of movement. She created costumes for George Balanchine, collaborated with artists Salvador Dalí and Marc Chagall, and dressed Vivien Leigh, Marlene Dietrich and Elizabeth Taylor on stage. In 1948 her costumes for the film Joan of Arc won an Oscar for Best Color Design.

This story is a vivid example of how women’s biographies and recipe records intertwine in cultural memory. The Karinska dessert and Solomiya Krushelnytska’s culinary notebook restore figures that had long remained in the shadows. At the end of the lecture Halyna Ohorchak urged visitors not only to read old recipe notebooks but also to share their own family recipes. After all, cuisine is a language that tells more about us than it might seem: it protects from oblivion, unites families and nations, and allows descendants to taste the flavours of bygone eras.

Postscript

For Olya Boiko, manager at the Ukrainian School of Hospitality, acquaintance with Krushelnytska’s home recipes became an example of how gastronomic heritage can inspire the modern restaurant business; it was a journey into another story about language, culture and memory and a confirmation that the language of service and the language of cookery need to be studied so that the future of hospitality can be built on a solid foundation from the past.